Noise and the developers

The impact of noise on development teams is a topic I’ve wanted to write about for a few years. We’re now in the midst of designing our new London office (Deloitte Studios) and this has become incredibly relevant. In our user research, acoustics is coming out as a very high priority. The backlash against open plan, and the poor acoustic experience this tends to deliver, is strong. It’s also giving us a great opportunity to explore this in more detail and test our hypotheses.

This post provides some background as to why noise matters for those who engage in deep focus work and how we can use this information to create a better environment for them.

To an outsider, the fact that a development team can be incredibly noisy and demand quiet seems like a paradox. If you work with, or near, developers then having an understanding of how deep concentration fits alongside broad collaboration will help you win friends.

The Deep

Let’s start with the deep concentration part.

When working with a code base, you’re trying to solve a problem. And you need to understand the context of the codebase to even begin to start solving the problem.

So the first thing a developer has to do is load the problem space into their head. And once loaded into their head, they need to keep it there. This can be a little bit like building a house of cards: it takes hours to build understanding and only a second to destroy.

It is the combination of the fragile nature of this ephemeral knowledge and the time it can take an individual to get into the flow that makes distractions and interruptions so costly.

I recall a day a few years ago, when working as part of a super productive development team working in a closed meeting room. The whole team was in deep focus, deep in the flow… and then someone put their head round the door and said, in a loud voice, “wow, it’s really quiet in here”. That cost the team the best part of a good afternoon of productivity.

Incidentally, “load time” is a great metric to understanding the maintainability of software. Some of the biggest productivity gains are made in reducing the “load time” —e.g. modular software, readability, comments.

So you want a quiet place then?

on [Unsplash](https://unsplash.com/collections/8989710/accoustic/1e397bd376accb37cd415b383ee0507d?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utm_content=creditCopyText)](https://images.unsplash.com/photo-1546953304-5d96f43c2e94?ixlib=rb-1.2.1&q=80&fm=jpg&crop=entropy&cs=tinysrgb&w=700&fit=max&ixid=eyJhcHBfaWQiOjF9)

Quiet places have their own social norms. In a large quiet room, like a library, there is a fear of making a noise. As conscientious people, we care about following these social norms and not disturbing others.

People often associate open plan offices with a high noise environment, but there are many open plan offices where the social norm is to follow library rules.

So where is the problem? Principally, it stifles collaboration. Software development is inherently a team game and teams need to talk. If you need to step out of your normal working area every time you want to discuss a piece of code or a specific problem… well, you’re having a bad day and the rest of the team might be losing out on useful information too.

And if you’ve ever sat next to a development team (or, if you’re part of a team, another development team) you’ll know they can be really noisy. Stand-ups, big design discussions, “who broke the build”. These are essentially for coordinating a large group of people and building a high performing team.

And so this is the paradox: teams are noisy but they want quiet.

Piecing it together

I’ve been lucky enough to work in development teams in a large variety of spaces. Everything from team rooms, through open plan, semi-open, partitions, basements, roof terraces, bars and even once at a stadium during a sound check — very distracting! Some have been great, some less great.

The most amazing spaces were the team rooms. We had the whole team working in a room, but it was isolated from the rest of the office. We achieved acoustic autonomy: the ability of the team to control the noise within their environment.

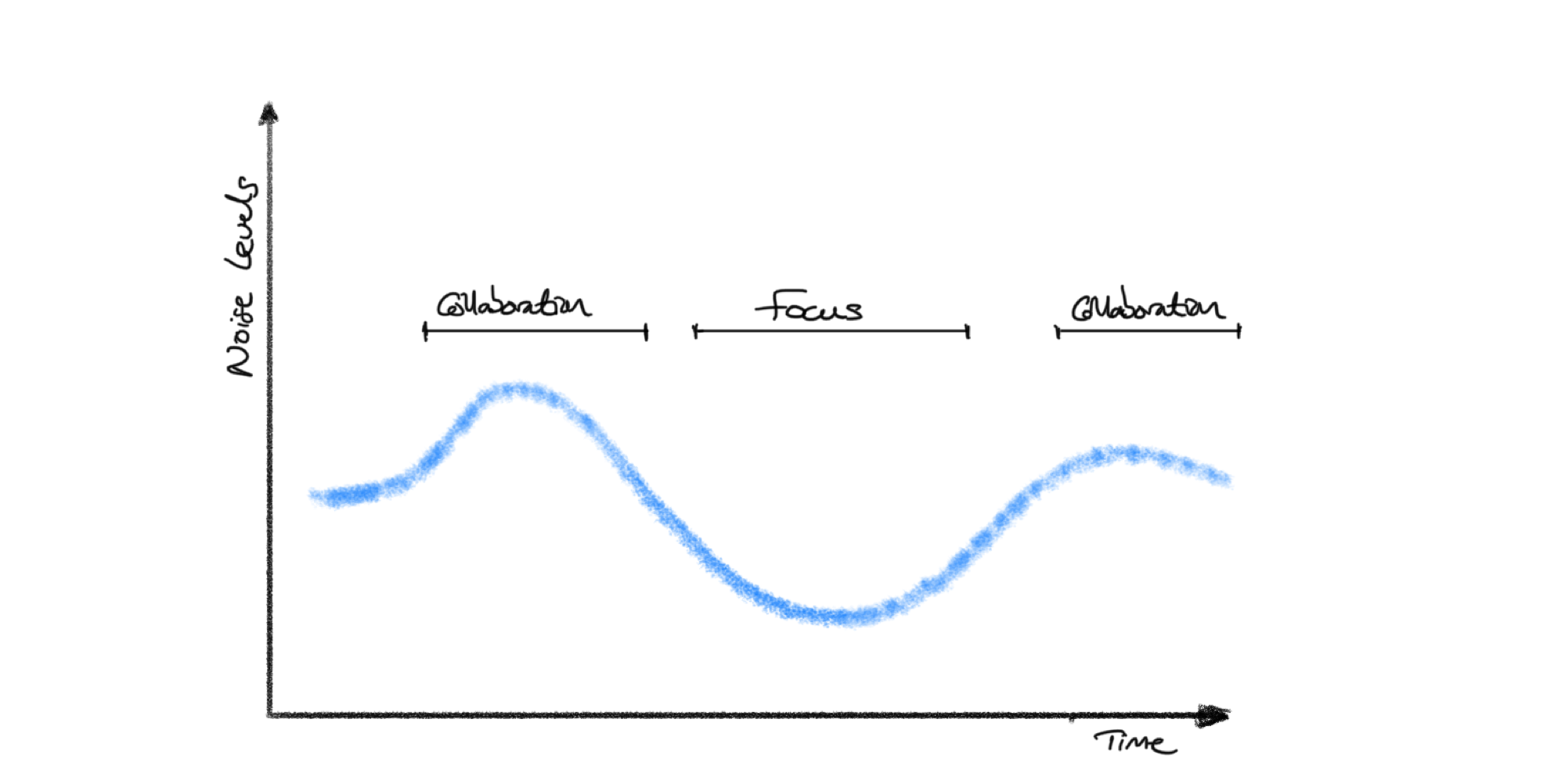

Where you do get this, you see an incredible thing: the team dynamically and organically shifts between quiet focus and loud collaboration, almost in a sine wave spanning the day:

And it’s magic. More productive, lower stressed, happier teams.

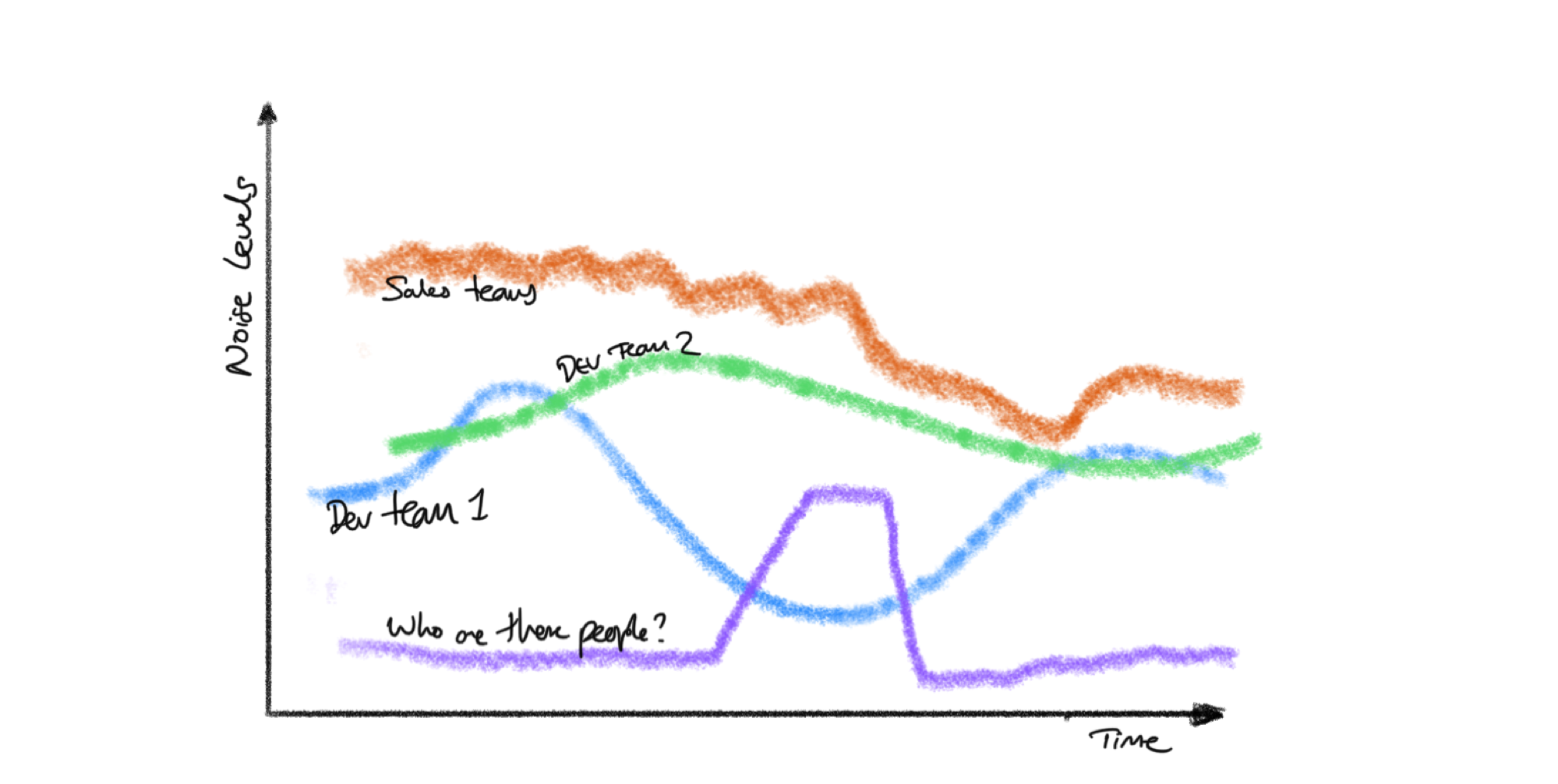

For comparison, an open plan office often feels like this:

This can lead to a space that is quite stressful and draining to work in.

When it gets bad, people take counter-measures into their own hands: working late, when there are fewer people in the office, or wearing headphones. Neither of these is a good thing. You may also see people vote with their feet and not come into the office.

A note on headphones

Is it cheaper to offer all new joiners decent Noise-Cancelling headphones? (a colleague on Slack)

I still maintain that headphones are a physical/cultural equivalent of a code smell. Yes, there are times it is best to block the world out and make a very deliberate signal of DND (alas, headphones aren’t universally recognized as this).

Of course there are exception. Individual preference may vary. Some people are way more sensitive to external stimulus than others, or may have tinnitus. So I’m not proposing a ban on headphones. But if you have to wear them to get anything done then there are probably some major acoustic and/or cultural challenges with your work environment.

I would argue that if everyone is wearing headphones then you’ve lost the benefits of the office. Consider going fully remote.

The new office

So how have we incorporated this into our design process for our new office?

This is still a work-in-progress and we are still learning, but there are few practical things we have already done:

We’ve set a clear objective that we should aim to build focus enabling environments (physical & cultural) that work for the people making the things.

We’ve elevated acoustic considerations to be a primary concern. This can be easily overlooked in plans the focus on how a space will look, and maybe how it feels. We’re now also asking “how will it sound” at every opportunity.

We’ve also developed some practical tests to evaluate acoustic solutions against to see if they meet our needs of acoustic autonomy. It required a test space, a test team, and some extras to play “other people” outside the space. The four tests are:

**Can we sit in the space and do focussed work? **We’ve found this is pretty easy to test in about 30 minutes. If people have headphones on them, wait and see if they resort to using them to gain focus.

**Are we comfortable having a full-volume collaborative conversation **If you hear the other teams impacting you, you don’t really want to annoy them, so the team quickly self-regulate and don’t have the open conversations we want.

**Can we dial in a remote team member into the space? **A common necessity is to have remote team members join in a conversation, either as part of a stand-up or as part of an ad-hoc discussion. Without this capability, we’d need to build more meeting rooms. This is a two part test: does it work from within the space?; does it impact people outside the space?

**Do we feel that we can control the acoustics of the space? **E.g. would we be comfortable playing music? Another easy test: take along some conscientious people, sit down for a while and ask if anyone feels comfortable playing music. This is perhaps a stretch goal but really gives teams the ability to control their space and create their own acoustic social norms.

Etiquette

I’ve got some pretty strong views on how people should behave in an office intended for focus work, particularly when you don’t have the luxury of a team room and are more in the open. These aren’t just my pet peeves: they are in response to observing how these behaviours impact development teams and interrupt focus.

It’s not about being library like quiet, but the social norms a quiet coach on a train is a pretty good starting point: turn off audible notifications and if you need to make a phone call please move to the vestibules (or phone booth in an office).

Phone calls are an interesting one, because often people do need to collaborate from their desks. I’ve paid some attention to this recently, and here’s what I’ve observed:

-

1:1 calls are usually fine, but conference calls or where the person is presenting are terrible.

-

People on the phone need to aware of how loud they’re being. If they have both ears covered, or buds plugged into both, that’s going to be hard and they’re likely to be too loud.

A surprise observation: noisy footwear on a wooden floor doesn’t make you friends. Tap-tap-tap of hard heels is very distracting.

And finally, speaking in a hushed voice when it’s otherwise quiet is probably a good idea.

In summary: respect. Observe, understand, be respectful and try to be tolerant of others.